As it was recently the 100th anniversary of the Representation of the People act, which gave women who were over 30 and property-owners, the right to vote in the UK, and will soon be Women’s History Month (including International Women’s Day on 8 March), the Sweet ‘Art team will be trying to see, and post about as many relevant exhibitions and events as possible.

First up was a visit to New Art Projects gallery in London for a panel discussion about their current exhibition Threesome. Threesome is an exhibition featuring artists Roxana Halls, Sarah Jane Moon and Sadie Lee, and has been curated by Anna McNay. The focus of the exhibition is the female gaze; each of the artists are figurative painters, female, and identify as queer. This follows on from the recent Tate show Queer British Art, which was a show timed to coincide with the anniversary of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act. This was a great show of art by gay white men, but was a bit lacking on other forms of queerness. Threesome was partly intended as a response to this – showcasing the work of three contemporary lesbian artists. I knew in advance that the premise of the exhibition was that each artist was painting each other as well as themselves, and had also each painted a nude study of performance artist Ursula Martinez. (Along with Corrina, and some of the fab WIA group, we had recently seen Ursula in discussion with Sadie at the National Portrait Gallery for their Queer Perspectives Lates).

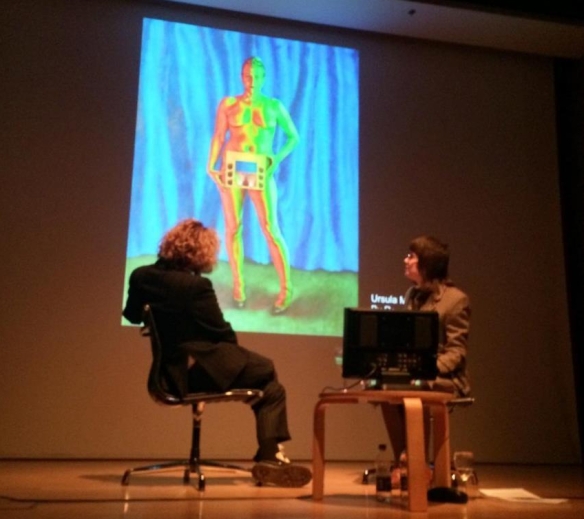

Sadie Lee and Ursula Martinez in conversation at Queer Perspectives

So I was excited to see the full exhibition, and the works ‘in the flesh’ (pun intended) rather than just as images. The event featured all artists and Ursula Martinez in discussion with Anna McNay, and the gallery has said that the full transcript of the discussion will be added to their website in due course. I highly recommend keeping an eye out for this! The discussion began with Anna McNay inviting each of the artists to discuss their works in turn, before moving on to the portraits of Ursula and finally opening up the discussion to encompass more general themes from the exhibition.

Portrait of Sarah Jane Moon, by Roxana Halls

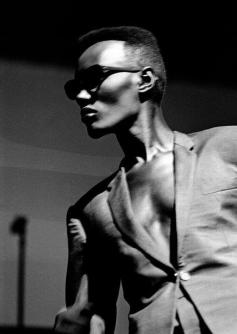

Each of Roxana Halls’ portraits use heightened colours (in the discussion she mentioned positioning her subjects within a set of neon lights to create the effect) and stylised poses reminiscent of dolls, to create what I would describe as a ‘nightclub’ effect. Her subjects are flanked by mannequins dressed as iconic lesbian characters from films and are posed almost as if they are mid-dance. For most of the discussion I was facing the portrait of Sadie, and (I don’t think it was just the fact that she was wearing glasses), I was reminded of some of the iconic images of Grace Jones. I attributed this mental link to the almost luminescent skin tones Roxana created, and to the strength and power of her images.

Bulletproof Heart album cover.

Ms Jones in 1984 in London, by Adrian Boot

In the discussion, Roxana said that she often uses mannequins within her work, not always so explicitly. Her reason for doing so is that straight male film directors will often use mannequins in their films to represent lesbian women; somehow implying that lesbian women are not quite ‘real’ women, or not quite human. Judith Butler says in her essay Imitation and Gender Insubordination “I suffered for a long time, and I suspect many people have, from being told, explicitly or implicitly, that what I “am” is a copy, an imitation, a derivative example, a shadow of the real”. This was echoed by the ideas present in Roxana’s work

The discussion of the use of the mannequin to represent lesbian women also made me consider the myth of Pygmalion, and the use of this trope in art and culture. Pygmalion was a sculptor who fell in love with the figure of a woman he had carved, and she was brought to life with magic and became his wife. The myth has been widely used in painting, film and literature.

Pygmalion and Galatea, by Jean-Léon Gérôme

Still from the film, Mannequin, dir. Michael Gottlieb

Still from My Fair Lady, dir. George Cukor (They changed the ending from the original play to add ‘romantic’ interest)

In both the straight and queer versions, these tropes appear to be created with the fear of the unknown, and the desire to impose control by not just objectifying, but actually making the woman into an object. The myth also places the creative agency in the hands of the male, whether that be the sculptor Pygmalion, shop-window dresser Jonathan Switcher, or linguist ‘Enry ‘Iggins. In these instances not only a creative, but a sexual power is also conferred to the male as in each instance, the bringing of the ‘mannequin’ to life results in sexual union.

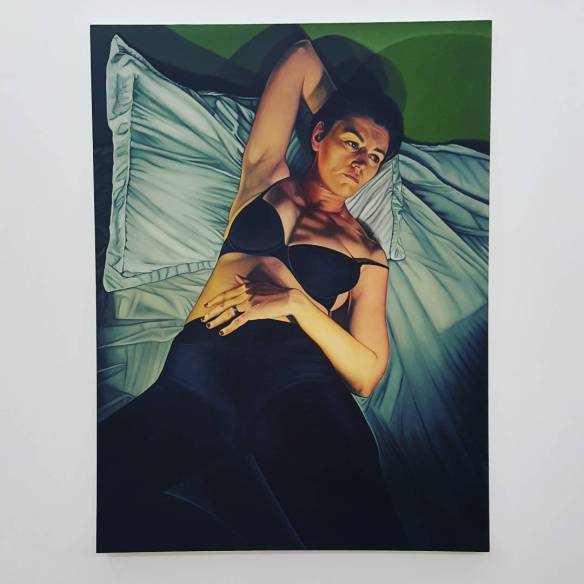

Portrait of Roxana Halls, by Sadie Lee

Sadie Lee’s work focuses on the ideas of intimacy and sexuality. Her three artist portraits are reclining figures, shown in their underwear, on rumpled beds. Within the discussion, Sadie said that her aim was to use (and I think to subvert) the traditional Venus pose, where the subject had one arm bent over her head, and another around her waist.

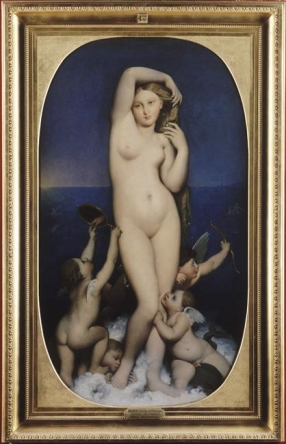

Venus Anadyomene, by Jean Dominique Ingres (with a barbie-doll genital area)

Venus Williams, taken by Hirakawa for ESPN Magazine

Her portraits were created by looking at the subjects from a position between the legs (described by Sadie as a position a lover might see them from), lit from below with a harsh raking light. They pick up qualities of the skin like dimples and stretch marks. The underwear is everyday; big knickers, 100 denier tights, bras with the label sticking out. In the discussion, Sadie said that she wanted the portraits to be real and mundane. She deliberately used a harsh light, to challenge traditional notions of female portraiture equalling female beauty. Her aim was to contest the thought that a portrait of a woman has to be flattering.

The portrait of herself was based on Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, where the model is purportedly using her hand to hide her genitals, but could equally be masturbating.

Sleeping Venus, by Giorgione,

Sadie’s self-portrait replicates this pose, but turned away from the viewer in order to make the pose “more threatening”. She explained that by turning her back on the viewer, she removes complicity in the voyeurism. The subject knows that the viewer is there, but is performing the act for herself and not them. Sadie’s portraits lie in direct contrast to the European tradition of the female nude, in which the subject displays her nudity for the observing male’s pleasure. John Berger sums this up in Ways of Seeing “In the art-form of the European nude the painters and the spectator-owners were usually men and the persons treated as objects, usually women. This unequal relationship is so deeply embedded in our culture that it still structures the consciousness of many women. They do to themselves what men do to them” – I really hope Venus Williams actively sought out her nude photoshoot of herself as a Venus!

Portrait of Sadie Lee, by Sarah Jane Moon

Sarah Jane Moon’s portraits were created with the aim of giving her sitters agency. The fact that they are all painters was important to her, and she wanted to show them as creators in their own right. Each of the portraits was painted from visiting the artist in their own studio, and the studio features as a backdrop. Each of the artists is also featured holding a tool of their painting. The subjects all stare back at the viewer, making eye contact which is direct and unapologetic and could even be described as challenging. The paintings show that in each case the viewed is also the viewer.

Self Portrait in a Straw Hat, by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Sarah’s portraits made me remember the self-portraits of Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, the 18th century French painter, and the thoughts of Griselda Pollock on this piece in particular. The artist has painted herself with the tools of her profession, but she is also portrayed as unambiguously female. She is well groomed, well dressed and beautiful. The shadow of her hat across her face and her gaze avoid confrontation. Her mouth is slightly parted in a demure smile. Pollock says that the aim of the piece is still to create a spectacle for us, the viewer, as through Western art history there has always been “an insuperable distance between the notion of the artist and the notion of a woman”.

Sarah’s pieces also critique the tradition of portraying the male artist in his studio, with his female (nude) model. In two of her portraits, we see completed works, or works-in-progress depicting naked female bodies. Within the discussion, it was revealed that one of the pieces behind Sadie was actually a self-portrait, further subverting the idea.

The Artist’s Studio, by Gustav Courbet

Lucian Freud, shot for Vanity Fair

Although each of the Threesome painters has a very distinct style, and is aiming to explore different things within their work, the discussion also drew out common themes. The idea of agency seemed very relevant. It seemed important to each of the artists that they were not simply producing a passive image of someone, but were creating a piece where the subject was active, dynamic and powerful – in some cases, stripping the viewer of their agency and relegating them to the role of passive consumer.

The discussion ended with the questioning of what is different about the female gaze. The panellists mentioned ideas of empathy, truth and respect; possibly even love, certainly from a queer female perspective. The point was also raised as to whether defining the female gaze was reductive. Is art created by women inherently different to that created by men? Should differentiation even be employed between art created by women and that of men?

Anna McNay, Sadie Lee, Sarah Jane Moon, Roxana Halls and Ursula Martinez in conversation

There was also the acknowledgement that the idea of the female is seen through a history of the male dominated society. Notions of femaleness, and queerness are both linked to notions of otherness, perpetuated in the Western art tradition, so what does being ‘female’ even mean – how can this be defined in a society which has always just seen ‘female’ in opposition to ‘male’ and ‘queer’ in opposition to ‘heterosexual’.

The theory of there being a somehow unified female gaze also implies that there is a shared way of looking which links women through history and across the world. Griselda Pollock also references these kinds of theories that art produced by women has commonality, saying that this idea will “…efface the fact that although women as a sex have been oppressed in most societies, their oppression, and the way they have lived it, or even resisted, has varied from society to society, and period to period, from class to class. This historicity of women’s oppression and resistance disappears when all women are placed in a homogenous category based on the commonest and most unhistoricized denominator”.

Many of these discussions and debates are far to large and unwieldy to continue here, but I am sure that we will touch on them again in our various exhibition visits. I also again recommend getting down to see the show for yourself before it closes. It is also running on conjunction with 3X3, also curated by Anna McNay, which is a photographic show from 9 queer female artists.

Threesome opened on 11 January 2018 and runs until 4 March 2018 at New Art Projects, London.